Navigating Change, Shaping the Future

The next economic shift will expose the unprepared.

We arm business and financial leaders with the strategic foresight to secure their future and the tactical insights and information to manage uncertainty.

EQ Workshops

Build strategic resilience. Detailed sessions designed to supercharge your knowledge of the business operating environment and future-proof your decision making.

EQ Briefings

Maintain operational agility. Pay-per-view analysis of the forces shaping the economic operating environment. Real-time insights you need to mitigate risks and manage with confidence.

Strategic Economic Issues

- Australia’s economy needs to be ‘match fit’ for a world of demographic change and rapid technological advances. Weak productivity, surging government spending and a rising tax burden are headwinds to growth, innovation and living standards.

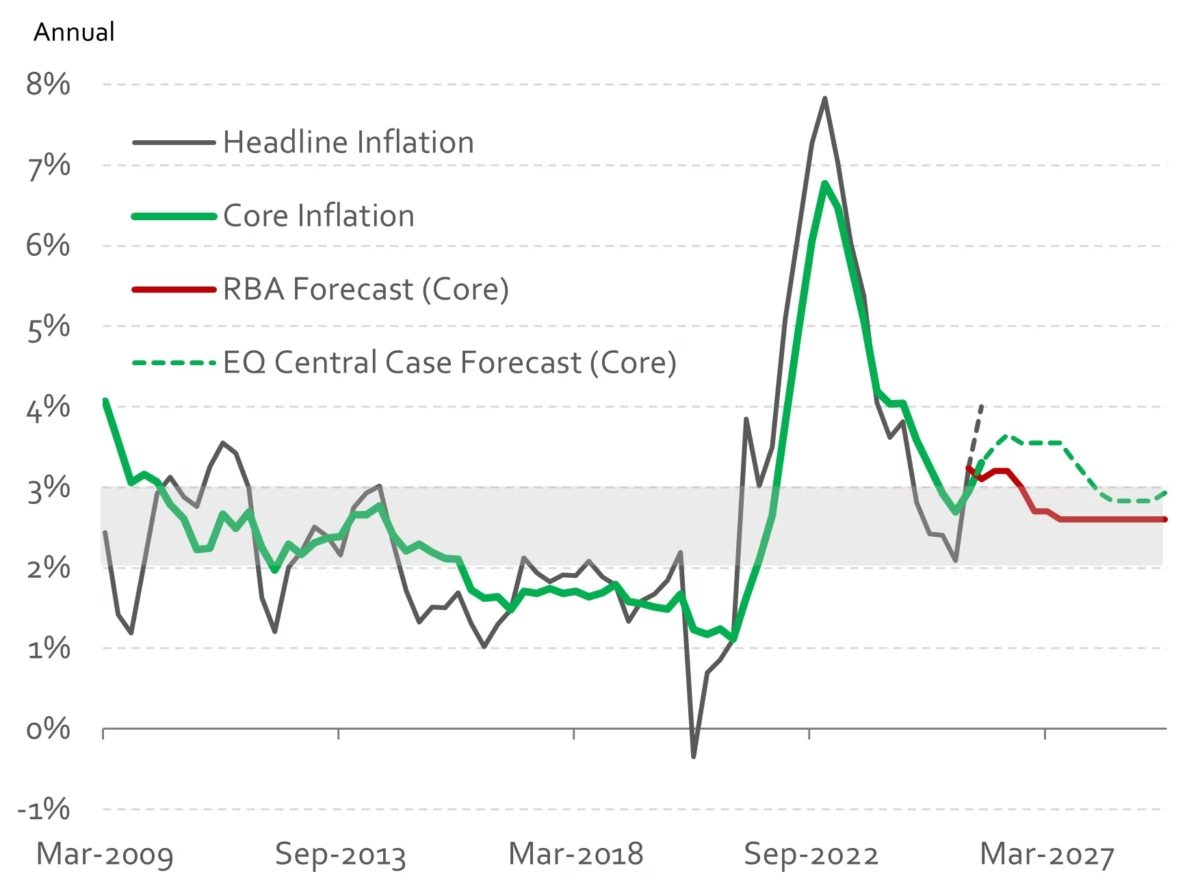

- Inflation is the immediate risk for Australia’s economy. The latest CPI numbers show inflation back above the top of the RBA’s 2-3% target band and likely moving higher into 2026. As an economy, Australia is highly exposed to inflation through variable rate mortgage debt and unindexed income tax brackets. It is imperative that the RBA keeps inflation low and stable.

- Geopolitical uncertainty, digital innovation and labour shortages are the big issues we can’t ignore, with energy supply and an onerous regulatory burden significant headwinds to investment and business expansion.

- We are in a world where innovation and technological uptake will be the major factor determining our economic success. Chronic labour shortages mean we need get people into the most productive and purposeful jobs. Australian business, big and small, will lead the way.

The New Economy of the 2020s

- Demographics is destiny, and demographic change is disruptive. The focus for many economists and policymakers has been on slowing population growth and an ageing population. But the most profound demographic change for our economy is the upturn in the dependency cycle, “the great demographic reversal”, as the UK economist Charles Goodhart phrased it in 2019.

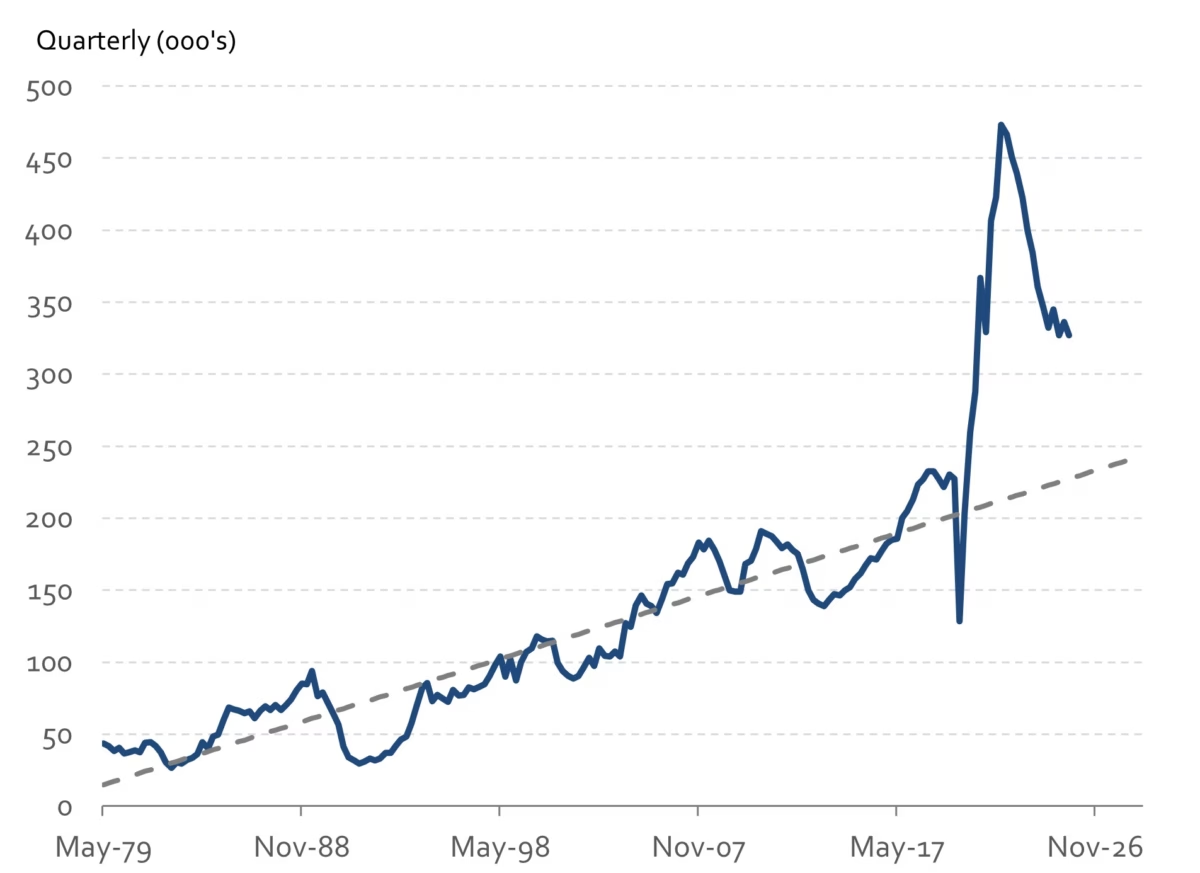

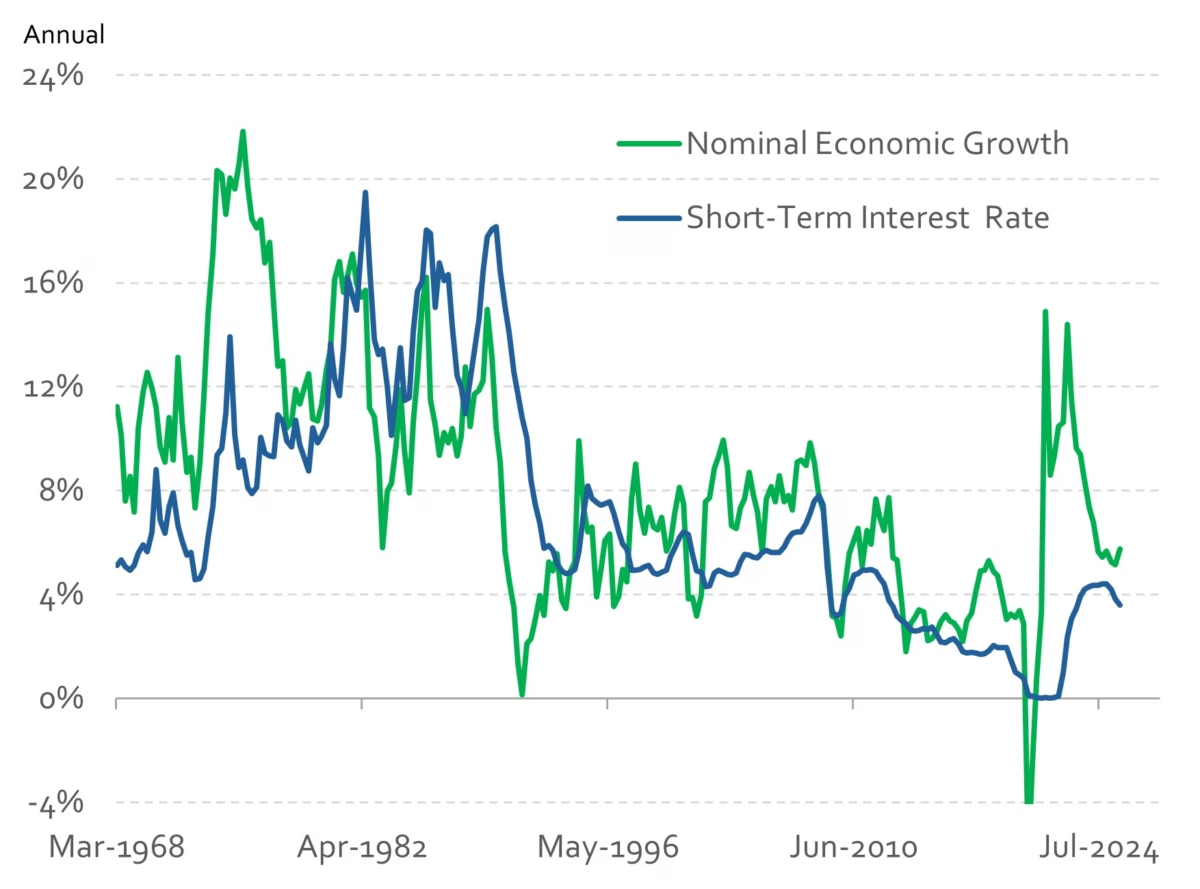

- After a half century of falling dependency, we are now have decades of rising dependency to contend with. We are at the beginning; but this new economy is emerging in front of our eyes. We have transitioned from a world of demand deficiency and unemployment to a new economy of excess demand and persistent upward pressure on labour costs and inflation. These are the macro outcomes, not well understood, and completely at odds with the economy we have known for decades. Critically, the emerging macro backdrop is a stark contrast to the economy immediately prior to the pandemic. But it is the microeconomic processes running through markets and industry that are fundamentally changing the business operating environment.

- Japan was the first nation to pass through this long-term demographic turning point. Outward foriegn direct investment and surging government spending characterised the Japanese approach to the great demographic reversal. Almost 20 years later the Japanese economy is vulnerable to shocks as government debt continues to climb towards 250% of GDP. The ‘Japan Route’ is not a viable option for Australia, but it could happen if government continues to grow it’s share of the economy, denying the market sector the resources and vitality needed to innovate.

- Utilising technology to enhance the existing labour supply or freeing up workers to move to human centred jobs, is the optimal path. The technology is coming online that can help all nations deal with these new demographic realities. Supercomputing and artifical intelligence will change everything over the decade ahead, and offer a world of high productivity, rising living standards and rapid innovation in everything from environmental managment to mental health.

- Our leaders must accept these new realities and manage the transition process to mininise the disruption to everyday lives and support those most impacted. To swim against this tide is to leave us all in a weaker position. As a general proposition, people resist change, not least our leaders. As a result, history is littered with sudden and severe economic crisis in the midst of these periods of social and economic transformation. Reality eventually catches up with those that resist. Whether it be an economic slump of its own accord, or a surge of inflation and interest rates, these economic crisis points rapidly reallocate our scacre labour and capital resources from the old to the new.

Chart of the Month

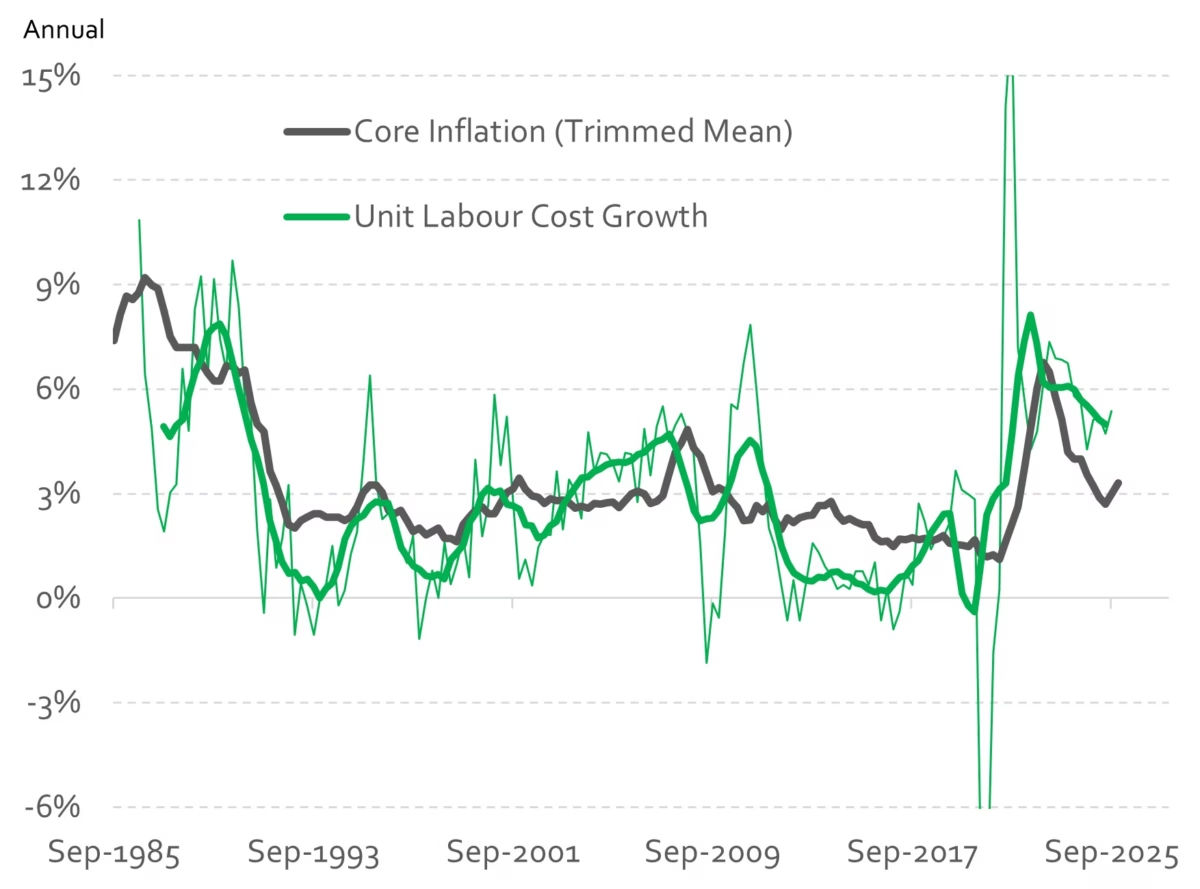

- Unit labour costs remain persistently high in late 2025

In the new economy of the 2020s structural labour shortages mean persistent upward pressure on labour costs. And that means persistent upward pressure on inflation - Australia’s cyclical economic recovery is well underway

For the RBA and interest rates this means we are entering an economic ‘danger zone’ where both cyclical and structural forces are putting upward pressure on business costs and inflation

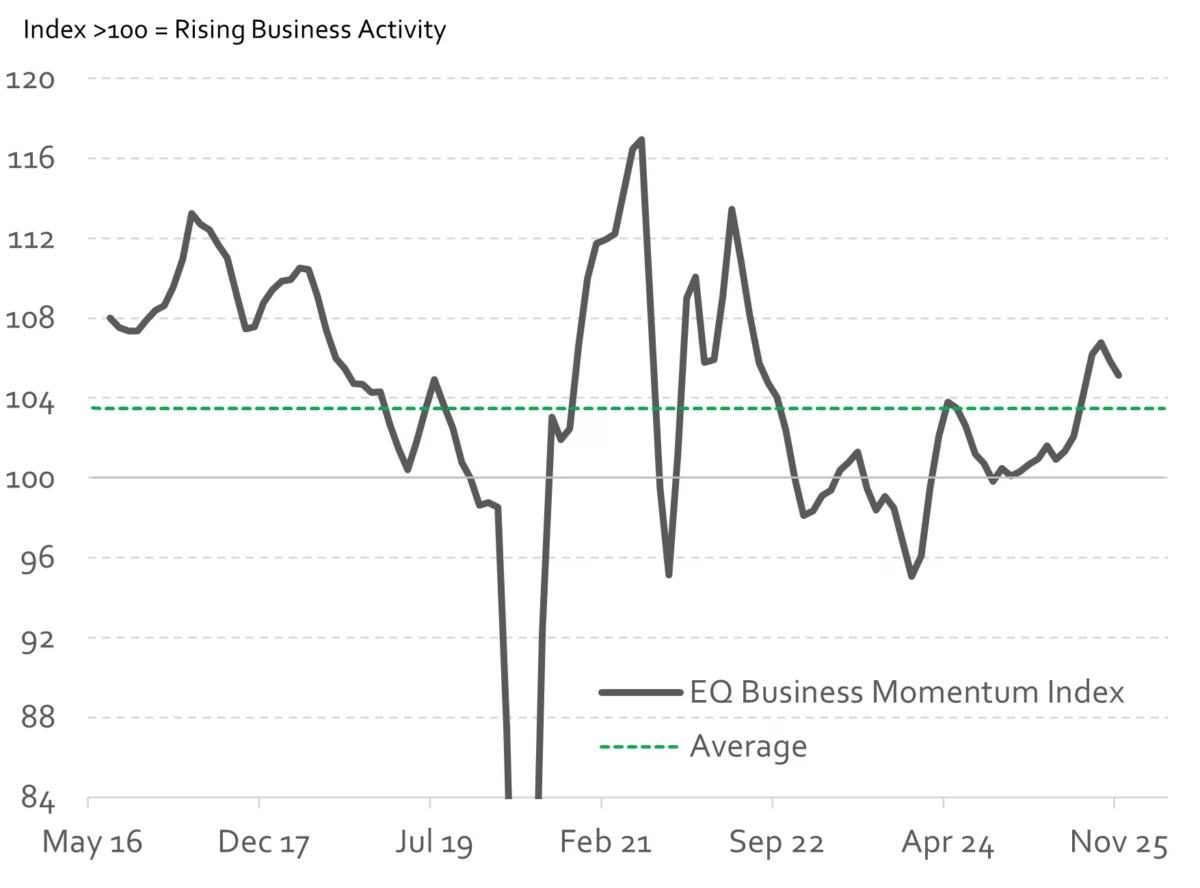

Key Business Metric

EQ Briefings – Timely Insight in an Uncertain World

Let EQ Briefings keep you informed in a volatile and uncertain operating environment. In a world where the economic climate has become more challenging, EQ Economics is committed to delivering clear, practical insights and expert commentary to help leaders anticipate change, respond with confidence, and navigate ongoing volatility.

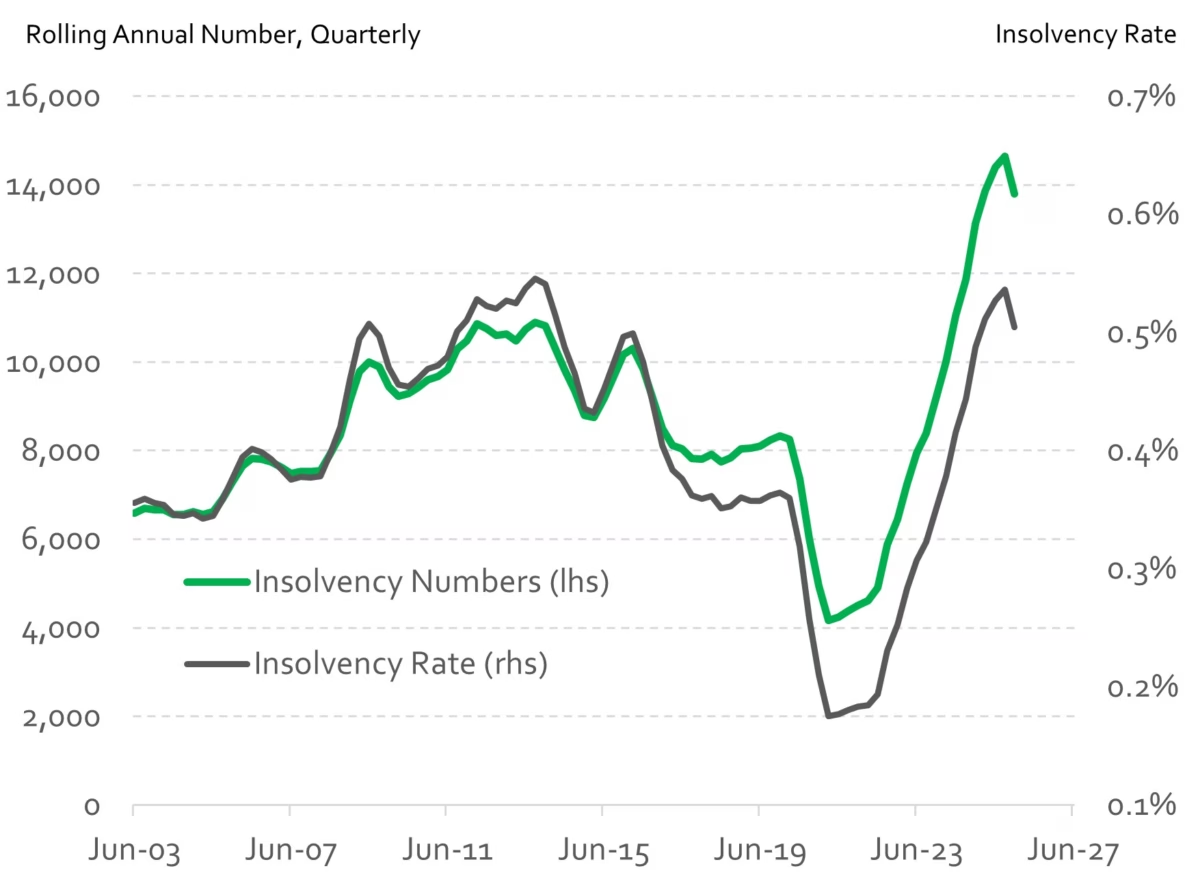

- Australian inflation has been rising since 1 July and is now well above the RBA’s 2% to 3% target range. Annual ‘headline’ inflation rate increased 3.8% over the year to October while core inflation is up 3.3%. The inflation data since July 2025 has been a genuine surprise to markets and economists but highlights better trading conditions for Australian businesses that appear to be able to pass on rising costs to final prices.

- At the December Monetary Policy Board meeting press conference the RBA conceded that some of the increase in underlying inflation is ‘persistent’, after months of downplaying the recent shift as ‘temporary’. A the December 2025 RBA meeting the board adopted a formal tighening bias for the first time in more than a year. The day of the RBA’s December board meeting a survey of economists showed just 1 of 30 expecting higher rates in 2026. Six economists expected rate cuts, with two institutions forecasting a February interest rate reduction. While the data has been highlighting inflation risks for six months, the group of market economists in Australia have not, influenced by RBA messaging and existing forecasts.

- The latest inflation outcomes combined with stronger economic activity are hard evidence that Australia’s interest rates are too low for current and expected economic conditions. The fact that inflation is no longer falling confirms that the ‘narrow path’ economic policy strategy of the RBA is not working – inflation never returned to target and is now entering a fifth year above target. This raises the very real question: if a 4.35% cash rate did not get inflation back to target in 2024, why would it in 2026? This point highlights the need for the RBA to get moving on monetary tightening by lifting rates at the first opportunity in 2026.

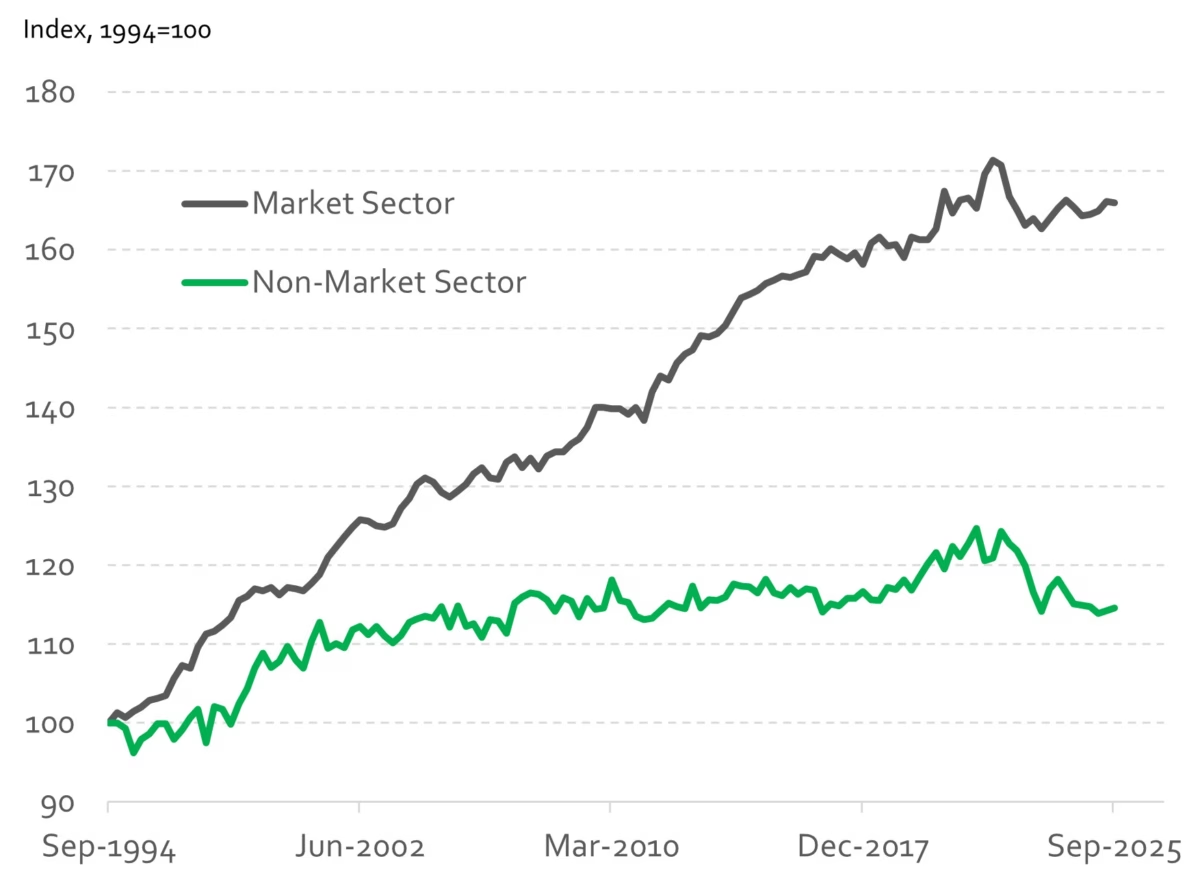

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates of market sector and non-market sector productivity reinforce the weak perfromance of the parts of the economy funded by government. The non-market sector is the public service and private sector industry reliant on government funding . These new figures are both illuminating and shocking.

- Non-market sector productivity in the September quarter of 2025 recorded an index level of 114.6. That is, over the last 30 years, public sector and government funded industry has seen a cumulative productivity increase of 14.6%, less than 0.5% growth per year on average. Over the last 30 years productivity growth of 1% per year would be regarded as OK in most advanced economies. Good productivity growth is considered to be around 2% per year .

- The market sector recorded a productivity index of 166 in September 2025, implying a 66% increase in productivity or just under 2% annual growth. This highlights a stark contrast between private business productivity, which mostly operate in competitive markets, and the public sector, where funding is mostly by governments.

- Market sector productivity is currently at the same level acheived in 2020, in contrast to non-market sector productivity that is at the same level recorded in 2005. That is another way of saying that the parts of our economy funded by government, and growing much faster than the overall economy for almost a decade, have not seen an improvment in productivity in 20 years.